By Imre Salusinszky

KEVIN Rudd knows he has to distance himself from the ugly face of unionism - as showcased this week by ranter Dean Mighell -- if he expects to win the election due later this year. But a survey of his own troops, especially in the Senate, confirms Labor's umbilical tie to the union movement. On the Labor side, the upper house resembles an elephant burial ground for "bruvvers". More than two-thirds of Labor's 28 senators have trade union backgrounds, with some having held more than half a dozen union jobs. Yet the vast majority of them are hiding their lights under bushels, with only two occupying frontline shadow portfolios -- legal affairs spokesman Joe Ludwig and communications spokesman Stephen Conroy. In Victoria, two of the three spots on the Senate ticket have been allocated to union-aligned candidates. Second spot on the NSW ticket has been given to Australian Manufacturing Workers Union chief Doug Cameron.

The above story appeared in "The Australian" on June 2, 2007

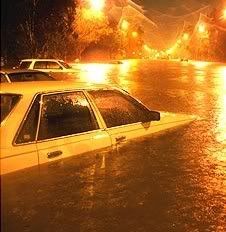

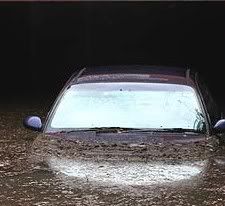

Downpours not enough to counteract disastrous Greenie limits on water storage

The rain keeps pelting down and causing widespread floods but with no dams built for many years little of it was caught and stored

The rain that has drenched eastern Australia this week is unlikely to ease suburban water restrictions or bring relief for farmers facing zero water allocations for the coming year. Snow will fall in the NSW alps for the opening of the ski season this weekend, but heavy rain is unlikely to reach the southern tablelands or Canberra, according to forecasters. Rain fell across the entire Sydney water catchment yesterday, including 10.9mm over Warragamba, which supplies Sydney's water, in the 24 hours to 1.30pm and 54.8mm over the Blue Mountains catchment. Most of it, however, just wet the dry earth. [Some of the "dry earth" can be seen in the pictures above. I am guessing that the car owners concerned would be wishing that the rain really HAD just soaked into the earth]

Combined dam levels were at 36.9 per cent of capacity -- 0.4 percentage points lower than this time last week. But the Sydney Catchment Authority is hopeful the forecast for more rain overnight and today will create much-needed run-off. The largest dumps occurred in the Hunter Valley, north of Sydney, where one station at Tocal received more than 100mm in two hours. Wyong received 75mm in one hour and Kangy Angy had 66mm in an hour. A number of areas along the Hunter coast received more than 200mm over the past three days. Wind gusts reached 106km/h yesterday near Newcastle, north of Sydney, and Fort Denison on Sydney Harbour.

The rain started in southeast Queensland and the north of NSW and has been slowly moving south. Forecasters expected the centre of the rain system to move to Sydney overnight and the Illawarra, south of Sydney, today. It should move east tomorrow. Queensland's dump of rain -- 30-70mm fell in 48 hours over most of the state's east, south and southeast -- has led to a slight increase in dam levels. The biggest falls were in the southeast, where Brisbane's catchments are situated. The falls were the best two days of rain since October 2005. South East Queensland Water storages rose from 18.22 per cent to 18.38 per cent, providing an extra seven to eight days' supply.

There may be more shower activity in the state's south later next week but by then weather in the catchment will again be dry and large run-offs are not expected. It is unlikely that the rain will have any impact on the need for tight water restrictions in NSW and Queensland.

Queensland households are on tough level-five water restrictions prohibiting sprinklers, hosing gardens and washing cars. In July, towns in the Murray-Darling Basin could be banned from outside water use. Prime Minister John Howard warned Murray-Darling Basin farmers in April they would receive no water allocations for the coming year unless substantial rain fell. Experts believe the downpours will not be enough to change the prognosis for farmers who rely on water from the basin.

Source. See also here and here

Vouchers are the way to go for Australian schools

They are the logical next step in improving education outcomes and would be a winner for the politicians who back them, writes Kevin Donnelly

WHAT is the best way to strengthen schools, raise standards and, in an increasingly competitive and challenging international environment, ensure that more Australian students perform at the top of the league table?

One approach, favoured by those with a vested interest in preserving the status quo, such as the Australian Education Union and the educrats responsible for the present parlous state of Australian education, is centralised and bureaucratic. Schools, especially government schools, are forced to conform to a top-down and inflexible system of command and control management where there is little, if any, room for autonomy at the local level, or flexibility in curriculum and developing more effective ways to meet the demands of parents and the marketplace.

The alternative, based on research identifying the characteristics of "world's best" education systems (as measured by international tests) and overseas innovations such as vouchers and charter schools, is to free schools from provider capture and to increase parental choice. Vouchers involve parents receiving an agreed amount of funding from government that they can then use to send their children to either government or non-government schools. The money follows the child and, as a result, good schools prosper and grow while underperforming schools face the consequences of falling enrolments and reduced demand.

Related to school choice is the need to ensure that how well schools perform, or underperform, is made public. When school effectiveness is clouded in secrecy, it is impossible for parents to make informed decisions about where their children go to school. At the minimum, all schools should be made to release details about educational performance, staff morale, absenteeism, student behaviour and, where relevant, indicators such as Year 12 results and post-school destinations.

Compare this to the present situation in Australia where, notwithstanding the rhetoric about identifying and turning around underperforming government schools, there are few, if any, consequences for failure and, as a result, thousands of students receive a substandard education.

Vouchers can either be universal or targeted at particular disadvantaged groups, such as children with disabilities or children educationally at risk because of their socioeconomic background. Vouchers can also either provide the full cost of educating a child, measured by the per-student cost of educating a child in a government school (about $10,000), or they can be set as a percentage, for example, by being means tested.

However, increasing educational choice by giving parents the right to choose where their children go to school is ineffectual if all schools, government and non-government, are forced to follow the same industrial-age management regime and dumbed-down, politically correct curriculum. The other side of the voucher equation is what in the US are termed charter schools. If schools are to be in a position to respond to community expectations, they need the autonomy and flexibility to meet parental demands. Charter schools, within general guidelines, fashion their own management style and curriculum, freed from the constraints of an intrusive and insensitive government-controlled bureaucracy.

As outlined in a 2006 paper prepared by the Australia Institute, titled School Vouchers: An Evaluation of their Impact on Education Outcomes, those associated with the cultural Left side of politics are staunch critics of freeing up schools and increased parental choice. The authors of the paper argue there is no evidence increased competition and autonomy improve educational outcomes.

An argument is also put that Australian society will become less cohesive as vouchers will lead to "greater segregation on the basis of race, religion, academic ability and socialeconomic status" and, based on the assumption that choice will lead to more parents choosing non-government schools, that state schools will be seen as second-rate and the least preferred option.

As might be expected, given that its continued survival depends on a centrally controlled, compliant state system of education, the AEU is also opposed to vouchers and the existence of non-government schools more generally. After criticising the federal Government's introduction of literacy vouchers, the AEU, at its 2005 federal conference, attacked opening schools to market forces by stating "the introduction of the voucher system of funding ... will ensure that much-needed government funding is directed away from those public schools with the greatest need into private pockets without any accountability requirements whatsoever". According to Pat Byrne, the AEU president, the Howard Government's policy of supporting parental choice is a ruse to destroy the state system.

It's ironic that supporters of state schools, such as the AEU, spend thousands of dollars on campaigns talking up government schools, under slogans such as "state schools are great schools", while arguing that introducing vouchers will lead to increasing numbers of parents fleeing the state system. Logic suggests that if state schools are as successful as their advocates make out, despite the introduction of vouchers many parents will still prefer state schools. The popularity of selective government schools in NSW and the fact that Victorian parents, if they can afford the real estate, are buying into areas with highly regarded state schools, proves that given a choice, parents will not necessarily "flee" the government system.

In his book Education Matters: Government, Markets and New Zealand Schools, Canberra-based economist Mark Harrison, in opposition to arguments about lack of effectiveness, details research showing that voucher-related choice and competition improve educational outcomes. Common sense also suggests this would be the case. If nothing else, the collapse of communism and the success of capitalism proves that the old days of statism have long since died and the most effective approach to government policy is to allow responsibility and decision-making to rest in the hands of those most affected, ie, at the local level. Harrison cites research undertaken at Harvard University into voucher schemes implemented in Washington and New York as concluding that "the academic achievement of voucher students who attended private schools grew faster than the similar students who did not receive a voucher and attended public schools".

Research evaluating the Milwaukee scheme arrives at a similar conclusion about the benefits of vouchers; instead of lowering standards or creating social fragmentation, there is evidence that not only are students' test scores improved, in addition, as Harrison states, "parents are highly satisfied, there was no creaming, parental involvement increased, the program targeted disadvantaged students successfully and reduced segregation".

Caroline Hoxby, a US-based academic and author of School Choice: The Three Essential Elements and Several Policy Options, on examining the results of the Milwaukee scheme, also argues that increasing choice and competition lead to improved results, as measured by improvements in students' mathematics scores.

Those supporting vouchers also make the point that improved standards are not restricted to schools enrolling students with vouchers; nearby government schools, given the reality of competition and the consequent incentive to improve, also register stronger results.

On identifying the characteristics of those education systems that achieve the best results in international mathematics, science and reading tests, Ludger Woessmann, from the University of Munich, reinforces the importance of choice and competition, especially as the result of a strong private school sector and decentralisation of management. Woessmann argues the market provides strong incentives for schools, as institutions, to provide a better service by meeting the expectations of parents and raising standards. If parents are not satisfied, they go elsewhere, and there are clear consequences and rewards for performance. While acknowledging the central role individual teachers play in successful learning, Woessmann also makes the point that those education systems suffering from provider capture, especially where teacher unions have an undue influence, underperform in terms of international test results.

While critics of vouchers, such as the AEU, emphasise that increased diversity and competition will only benefit so-called wealthy, elite, non-government schools, it is significant that American voucher schemes focus on supporting disadvantaged groups such as Hispanics and African-Americans. Such is the success of these schemes in addressing educational disadvantage, as noted by Terry Moe, a researcher at the Hoover Institution, that "in poll after poll, the strongest supporters of publicly financed vouchers are blacks, Hispanics and the poor, especially in urban areas".

As the 30 to 40per cent of Australian parents who send their children to non-government schools are well aware, debates about vouchers are of more than academic interest. Not only do these parents pay taxes for a system they do not use, thus saving state and federal governments millions of dollars each year, hard-earned cash has to be found to pay school fees. The reality is that parents who, as a result of the perceived shortcomings in government schools, choose non-government schools are financially penalised. While state and federal governments support such choice by partially funding students attending non-government schools, the amounts provided are well short of the costs involved and the system lacks the preconditions necessary for an effective voucher system.

On the grounds of equity and social justice, it makes sense if more parents, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds, are able to choose between government and non-government schools. Ideally, such a voucher would be set at $10,000 and the money would follow the child. Vouchers and charter schools, reflecting a commitment to choice, competition and accountability, present new territory in the education debate. At first glance, such initiatives are a natural fit for the Howard Coalition Government and, given the cultural Left's antagonism, something traditionally opposed by the ALP. As such, vouchers and charter schools provide one policy area where there are clear differences between the two parties and fertile ground for public debate.

Source

Vouchers are the way to go for Australian Universities too

Comment by Steven Schwartz, the vice-chancellor of Macquarie University

The Group of Eight universities has launched a far-reaching higher education policy statement and, again, educational vouchers have been thrust into the spotlight. Ever since the Nobel economics laureate Milton Friedman suggested funding education with vouchers in 1955, the idea has surfaced periodically in Australia only to be met with howls of rage from education unions and yawns of apathy from everyone else.

There are three reasons this time could be different. First, educational vouchers can no longer be dismissed as impractical. School voucher systems operate successfully in several countries and a university voucher system has been introduced in Colorado. Second, both sides of politics are committed to a diverse system of higher education. By forcing universities to find a competitive niche, vouchers foster diversity more effectively, and certainly more efficiently, than the present system of centralised formula funding. Third, it has previously been taken for granted that vouchers would be politically unpopular because they would have to be rationed. It was feared that promising everyone a voucher would lead many extra students to enrol, thereby causing a budget blowout. But times have changed. There is no longer any need to worry about hoards of frustrated students queuing for vouchers because, the Government says, there is no longer any unmet demand.

Everyone who wants to attend university is already being admitted. Unless it decides to be uncharacteristically generous, a universal voucher entitlement would cost the Government no more than the block grant system. Vouchers would overcome anomalies inherent in the present funding arrangements by introducing rudimentary market forces into a system that operates according to Government fiat. At present, universities have little ability to respond to student demand. The quota of Government-subsidised student places at any university each year is determined by history: universities get about the same number they received the previous year, with small adjustments.

We know that students prefer some universities to others. However, even if they wanted to, popular universities are prohibited from expanding their intake to meet student demand. Indeed, like plant managers in the old Soviet Union, university managers are punished if they enrol "too many" students. As a result of quotas, many qualified students are turned away from their university of first choice. They are forced to try their second, third or even fourth choice, until they finally find a university that will admit them. By limiting the number of places in any university, the Government makes it impossible for universities to expand their intake in response to student demand. It is a way to protect less popular institutions whose students might go elsewhere if given the chance.

Giving funding to students in the form of vouchers and eliminating quotas would allow universities to adjust supply to meet demand. But vouchers would not be enough. To ensure the highest levels of excellence, they would need to be combined with the deregulation of university fees.

At present, the amount students pay through the Higher Education Contribution Scheme is largely determined by the Government; universities have limited leeway to charge more. Yet, they are in competition with generously funded competitors from around the world. If we want to compete in the premier league, we have to direct resources to those institutions that achieve the highest standards of excellence. Lifting the cap on student contributions would allow our best universities to raise their fees; this would bring them the additional resources they require to compete with the world's best. To ensure that access to elite higher education institutions is not limited to the rich, universities that raise their fees should be required to spend some of their new wealth on income support for needy students.

In reality, however, only a small number of institutions would be able to charge premium fees and provide exceptional services. Many would go for low price and high volume. Other models would also develop. Some universities would offer vocational and technical types of education. Others would focus on distance learning. Some would deliberately focus on a small number of programs that met student needs.

Under a voucher system, universities would have to be attractive to students because that is the only way they would receive any resources. Students would benefit because they would control the purse strings and would therefore be able to influence what was taught, by whom and when. Institutions would benefit by being able to adjust their offerings to meet student demand. Most of all, Australia would benefit from having stronger world-class universities to produce the graduates we will need to ensure social and economic progress.

Source

His Eminence upholds Catholic orthodoxy without fear or favour

He is wise to do so. It is the wishy-washy churches that have empty pews

Comment below by Christopher Pearson

It should have come as no surprise to anyone last week when George Pell announced he would ask principals in Sydney's Catholic schools and teachers in charge of religious instruction in his diocese to affirm their loyalty to Catholic doctrine. He wants them to swear an oath of fidelity to what the church teaches, with specific reference to various issues of sexual morality and an exclusively male priesthood. But the theological modernists who've long ruled the roost in Sydney were appalled at the idea of a bishop taking orthodoxy seriously and expecting the people responsible for the formation of young Catholics to do likewise.

They voiced their indignation in the secular media and fringe Catholic magazines, as modernists and ultra-liberals have been doing since the Second Vatican Council. However, on this issue the boat-rocking exercises met with limited success. I expect most non-Catholics don't much care one way or the other and there's also a matter-of-fact general acceptance that every club has its rules and members in good standing abide by them.

Later in the week, Pell put himself in the line of fire a second time by issuing a statement about embryonic stem cell research, on behalf of the Catholic bishops of NSW. It was essentially a collegial response to contentious legislation rushed into the NSW parliament. But it was also another pretext for the cardinal's clerical detractors, The Sydney Morning Herald and the ABC to brand him as an authoritarian zealot.

Sydney's Anglican Archbishop Phillip Jensen condemned the bill just as forcefully as Pell did. The research the bill was designed to give licence to was compared to the unethical developments of Nazi scientific experiments. He also warned that, if passed, the bill would "enshrine in law the corrupt view that the embryos used are not morally significant or important". Despite that, Jensen was left unscathed, on this occasion at least, and almost all the media attention was on the cardinal.

The statement Pell had issued was unobjectionable. "No Catholic politician, indeed no Christian or person with respect for human life, who has properly informed his conscience about the facts and ethics in this area, should vote in favour of this immoral legislation."

One of the main responsibilities of bishops is to teach their people precisely so they can develop their individual consciences, informed by sound doctrine rather than in a moral vacuum. There is an even weightier responsibility when telling Catholic politicians, who have to vote on contentious moral issues, what the church's position is. This is especially the case, as was obvious last week, when they are ignorant and not very observant Catholics, indifferent to the church's teachings when they are politically inconvenient.

No Catholic theologian of any consequence has argued in favour of human embryo cloning, or creating embryos with three or more genetic parents, or creating human-animal hybrids for testing purposes. Although these procedures raise new issues, in the sense the science itself is new, they are experiments that contravene fundamental tenets regarding human procreation. No consequentialist argument, based on possible miracle cures down the track, could trump first principles.

Pell tells me that when The Sydney Morning Herald's Linda Morris attended his press conference, she had given advance notice of two questions on the subject of excommunication. He told the press, as she duly reported the next day, that he wasn't threatening Catholic politicians who chose to support the bill with excommunication. But he did say there would be "consequences in the life of the church" for those who voted for the legislation.

Consequences short of excommunication were once widely understood, both by Catholics and most religiously literate adults. They ranged from the risk of disapproval from other people in the pew and earnest entreaties to think things over by the clergy to stern words from your confessor, if you availed yourself of the sacrament of penance. He might withhold absolution until there was some sign of contrition or even advise against going to communion until you had acknowledged the error of your ways. Such consequences, which these days would perhaps weigh only on a delicate conscience but still reflect the seriousness of the offence, fall a long way short of medieval declarations of anathema, with bell, book and candle, as the saying goes.

There has recently been a lot of (mostly ill-informed) media hype on the issue of excommunication. Raymond Burke, Archbishop of St Louis in the US, caused a great stir when he said he would refuse the sacrament to Catholic pro-choice Democratic candidate John Kerry in the lead-up to the previous presidential election.

On the plane to Brazil, Pope Benedict XVI told an interviewer that, in some cases where people were directly involved in assisting at an abortion, they automatically excommunicated themselves. This was the case in a technical sense, known as latae sententiae, whether or not the church formalised the matter by announcing it.

Voting in support of cloning is a serious matter, although not in the same grave category as participating in an abortion. Still, it is hard to imagine how any of the notionally Catholic MPs, of whatever party, who voted in favour of the bill could imagine themselves as being in good standing in their membership of the church. For all that, press speculation about possible excommunication combined with Pell's warning of lesser consequences had them waxing righteously indignant about threats and "bully-boy tactics".

NSW Premier Morris Iemma said he "wouldn't take kindly to being denied communion", as though it were a simple matter of entitlement. His deputy John Watkins said he was "a bit mystified by the authoritarian view" put by the cardinal. Frank Sartor, the NSW Planning Minister, went one better and described Pell's comments as "reminiscent of the Dark Ages".

Federal Employment and Workplace Relations Minister Joe Hockey decided to buy into the argument, even though it was a state issue. He offered, for all the world as though he'd given the matter great thought, the line: "I don't object to Pell expressing that opinion, but I do object to any suggestion that there are consequences."

As the cardinal noted in an article on Friday in The Sydney Morning Herald, actions do have consequences, as any politician who crosses the floor soon finds out. I was heartened to see NSW Liberal leader Barry O'Farrell undertook to consider what Pell had said and refrained from grandstanding. The Nationals' Adrian Piccoli couldn't resist boasting: "I would like to see them try and stop me taking communion."

NSW Emergency Services Minister Nathan Rees made the silliest contribution so far from a serving politician. He objected to what he called Pell's "emotional blackmail", saying: "The hypocrisy is world class. No government would seek to influence church teaching when providing taxpayer funds for the refurbishment of St Mary's Cathedral or the education of Catholic school children or to subsidise rates exemptions for churches." He also raised the possibility of referring the cardinal's remarks to the house's privileges committee: "I consider Cardinal Pell's incursion a clear and arguably contemptuous incursion into deliberations of the elected members of the parliament."

The debate hasn't reflected much credit on many of the Catholic politicians in the NSW parliament. Nor does it show the quality of instruction they received in church or in Catholic schools in a flattering light. It's clear many of them don't know the first thing about what their church teaches on life issues and don't regard themselves as being under any obligation to take notice when it's pointed out to them. They have a convenient and strangely Protestant notion of the sovereignty of conscience - shared, it seems, by Jesuit priest and academic Frank Brennan - and somehow imagine "everyone's entitled to their own opinion" in matters of faith and morals. There is a theological term for this. It's called "a condition of invincible ignorance".

When I spoke with Pell in the middle of the brouhaha, he sounded a bit saddened but not at all surprised by the turn the debate had taken. "All this talk of excommunication is a distraction from the main issues. No amount of political bluster will change the fact that this bill is an assault on human life, for gains which are so far nonexistent. Everyone claims to believe in the sanctity of human life. We really mean it."

Source

Australian Politics

Australian Politics

Evelyn Rae, a conservative Australian political commentator

Evelyn Rae, a conservative Australian political commentator

Margo Robbie -- a beautiful australian

Margo Robbie -- a beautiful australian

My son Joe at ANU

My son Joe at ANU

One of the happiest pictures ever -- Cleo Smith, aged 4

One of the happiest pictures ever -- Cleo Smith, aged 4

No comments:

Post a Comment