Money doesn’t grow on trees

By Sara Hudson

Opposition Leader Tony Abbott’s decision to support Indigenous Affairs Minister Jenny Macklin’s income management bill signals a much-needed change in attitudes to welfare in Australia.

When I was young, my mother would often say, ‘money doesn’t go on trees’ in response to my pleas for her to buy me something. Today, when I tell my own children that I can’t afford to buy them something, their response is, ‘So why don’t you use your credit card?’ Teaching children that there isn’t an endless supply of money from a hole in the wall or a plastic card is one of the tasks of parenthood.

By the time they leave home, even if children haven’t quite grasped the fact that money is something you have to earn, they soon do. Generally, most people wake up to the painful reality of working for a living and the effort required to earn their dollars.

However, it’s a different story for those who have never had the experience of working. It’s a sad reality, but the more the government gives without expecting anything in return, the more people tend to expect that the government will meet their every need. Many develop a strong sense of entitlement about what the government ‘owes’ them – and the sense of individual responsibility weakens and dies.

Macklin’s decision to extend income management across the entire Northern Territory, regardless of ethnicity, and eventually on a national basis to individuals who meet certain criteria, is a good one. There needs to be a differentiation between money earned and money received from the government. If people have less freedom regarding how they can spend their welfare payments, then maybe it will make them think harder about the advantages of working.

For those who haven’t learned the skills of budgeting, income management ensures that at least some of the welfare payment goes towards essential needs – like food for their kids. Unfortunately, too many children in Australia know what it means when their mum says she hasn’t got any money – waiting until dole day to get a decent feed. Sure, income management is paternalistic – but in this case, it’s a necessary evil.

Tackling the insidious effects of passive welfare requires some ‘tough love.’

The above is a press release from the Centre for Independent Studies, dated March 19. Enquiries to cis@cis.org.au. Snail mail: PO Box 92, St Leonards, NSW, Australia 1590.

Battle looms over cuts to history curriculum

As a 5th generation Australian who is mightily pleased to be an Australian, I don't think I can be accused of ill motives in what I am about to say but I do think that the teaching of Australian history can be overdone. It is a very praiseworthy history but it is small beer on the world scene. American, British and European history are far more important for study in schools

WRITERS drafting the national curriculum need to reduce the amount of Australian history taught - raising the spectre of another fight over what is cut when the document is finalised later this year. The chairman of the Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority, Barry McGaw, told the Herald that he was open to reducing the history content in response to concerns that it contains too much for teachers to cover. Professor McGaw said he was "open to any advice the history teachers want to give to us". "We need quite specific advice," he said. "They need to say what needs to come out."

The president of the Australian History Teachers Association, Paul Kiem, said feedback from around the country confirmed the draft curriculum was too content-heavy, particularly in years 9 and 10 when the bulk of Australian history was taught. "There has to be some culling," he said. "There needs to be a pause and discussion about what is significant knowledge in Australian history and what we expect people to know by year 10. "Australian history dominates years 9 and 10 and it is one area in which decisions will have to be made about reducing content or introducing options."

Drafters of the curriculum, which is open for public consultation until May 23, have so far satisfied a range of political interest groups by covering as much as possible within a framework of 80 teaching hours each year. Some also believe there will not be enough time to teach world history in the depth outlined in the draft curriculum. At present, NSW is the only state that tailors its curriculum to a specific time frame: 50 hours for history.

Those involved in the curriculum drafting have confirmed the history outline is overly ambitious and will need to be condensed, have topics removed or have core areas taught as electives. Teachers believe the curriculum authority is nervous about stirring up political tension over which topics it will remove.

The NSW Board of Studies and the state government have been silent on any contentious national curriculum debate issues this federal election year. Mr Kiem said his and other teacher organisations were frustrated at the silence of state and territory Labor governments. "It is a very significant problem," he said. "There is no transparency. No one is saying how many hours we will have to work with. "We have been saying for a long time that we need to get a response … about implementation and from universities about teacher training. If we don't get answers from state and territory governments, there will be inconsistent implementation."

Mr Kiem said he was concerned that the national curriculum authority was not open or flexible enough to offer core history curriculum in the form of options. "We are looking at a document that can be implemented flexibly," he said. "My impression with ACARA is that there is a generic template approach to designing the curriculum, the notion that all students will be studying the one history course. There is a real need to consider those implementation issues. What is needed is flexibility. How you do that is develop core and options."

A spokeswoman for the NSW Minister for Education, Verity Firth, declined to comment on details of the history curriculum. "From day one, the NSW government has supported the development of the national curriculum and we are currently examining the details of the draft," she said.

SOURCE

The grammar you teach when you are not teaching grammar

The gobbledegook below sounds like a face-saving way of admitting that the abandonment of grammar teaching was a big mistake

THE problem is huge: low levels of literacy among up to half of Australians. The solution: a new national school curriculum, literacy for the 21st century and, gasp, grammar.

Some say dropping grammar in the 1970s began the slide to today's textese - "yng peeps cant rite proply".

But many older Australians live with literacy levels lower than young people. The issue is the needs of people and the economy are changing and so is the curriculum.

Is boring old grammar the answer? Well, not really. It's a modern approach to grammar that's being introduced. And the ambitions are broad: lift children who slip through cracks in the education system to a level of reading and writing that reflects Australia's wealth.

Almost half of adult Australians have literacy skills lower than those needed to meet the demands of everyday life and work in a knowledge-based economy, Bureau of Statistics figures show.

Scarily, nearly two-thirds of those whose first language is not English scored below the minimum.

Even so, compared with other countries, Australia rates well on high-school students' scores in reading, maths and science tests. The problem is that achievement differs across the country - and between the disadvantaged and the better off. Last year's national tests reveal nearly one in three year 9 students in the Northern Territory is below the minimum standard in reading, writing, spelling and grammar and punctuation - they do not have rudimentary literacy skills. In NSW, about one in 10 students is at this low level.

The draft national curriculum puts grammar, spelling and punctuation at the centre of English teaching and learning. But why now?

Grammar was cut in the '70s because of a view it didn't help students' writing, said Dr Sally Humphrey from the University of Sydney's linguistics department.

"It was like, 'We're just going to give you building blocks; we're not going to show you how it works in text."' The grammar starring in the new curriculum "isn't a set of rules for 'correct' use", she said, but "a set of resources or a tool kit" to be used according to the situation - whether it's texting, giving a presentation in class or writing a history essay.

"Each of those three situations would require different resources, different patternings of grammar, to do the job properly in that particular context," Dr Humphrey said. "We want to give kids the grammatical resources for being able to do lots of different things."

Reintroducing grammar was also part of an effort to strengthen the literacy of children from multilingual and disadvantaged backgrounds, said the lead adviser to the new English curriculum, Professor Peter Freebody from the University of Sydney. "Our teachers and our systems are geared to doing well for the mainstream," he said. Imagine that school results, including literacy, are shaped like a tadpole. The fat body, representing the bulk of students, does well or quite well. But there's a long tail of people left behind.

Professor Freebody said students didn't learn to read by year 3 and then just build content knowledge. Different kinds of texts demanded different understandings, he said, "and those things don't come free with the territory just because you're good at reading and writing when you're in year 3".

While grammar's return may sound like going back to the '50s, the modern educator's knowledge of grammar, and its use for teaching "reading and writing and enriching kids' understanding of content areas, that's not going backwards", Professor Freebody said.

The new curriculum was arranged into three strands - language, literacy and literature - with grammar an "integral component" of each strand.

It's about "letting kids in on the 'secret' of how good writers and good text producers do their work through the resources of language, through the resources of grammar - 'hey, this is how it's done!'," Dr Humphrey said. "And that's an equity issue … Kids who haven't got access to middle-class homes and middle-class ways of using language that are valued in the schools, they do need [the workings of language] made explicit."

The Australian Industry Group has highlighted the negative effect of low literacy and numeracy on productivity, safety and training. Group chief executive Heather Ridout said the new curriculum was "a long overdue step, so we're strongly supportive of it". Ms Ridout stressed the need for more specialist expertise in language across the board. "We don't just not have it in schools; we don't have it in TAFE, in the VET sector, and we don't have it in the workforce."

SOURCE

Is there any unmassaged climate data out there?

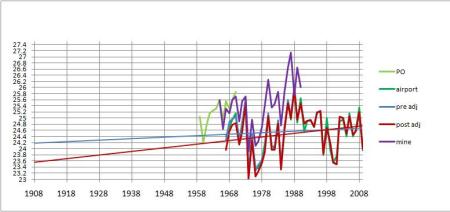

This is yet another example of things that don’t add up in the world of GISS temperatures in Australia. Previously, we’ve discussed Gladstone and Darwin.

Ken Stewart has been doing some homework, and you can see all the graphs on his blog. Essentially, the Bureau of Met in Australia provides data for Mt. Isa that shows a warming trend of about 0.5 degrees of warming over a century. GISS takes this, adjusts it carefully to “homogenize urban data with rural data”, and gets an answer of 1.1 degrees. (Ironically among other things, “homogenisation” is supposed to compensate for the Urban Heat Island Effect, which would artificially inflate the trend in urban centers.)

To give you an idea of scale, the nearest station is at Cloncurry, 106km east (where a flat trend of 0.05 or so appears in the graph). But, there are other trends that are warmer in other stations. Averaging the five nearest rural stations gives about 0.6 degrees; averaging the nearest ten stations gives between 0.6 and 0.88 degrees.

Mt Isa and surrounds with temperature trends

But, they increase the slope of the trendline from less than 0.5 to more than1.1 degrees Celsius per 102 years by lowering the earlier data by 0.3C. They say they do this because they homogenise urban data for discontinuities caused by station shifts, Urban Heat Island (UHI), etc., by their stated method: “…[U]rban stations are adjusted so that their long-term trend matches that of the mean of neighboring rural stations. Urban stations without nearby rural stations are dropped.” ( http://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/)

The Mt Isa Graph

The Giss (red) line shows a steeper warming trend, because earlier data is adjusted down.

But in the end, the temperatures don’t fit linear trends very well. In Bourketown, for example, there was a rise, but it was mostly during 1945 – 1988, and in the last twenty years, as Ken points out, there has been a significant fall.

Burketown 327km north east

By themselves, these minor revisions wouldn’t be worth getting excited about, but the fact that they keep occurring and that they are so blatant and always in a warmer direction surely becomes too many nails in the coffin.

One can only assume that the people “adjusting” never thought anybody would check. And if billions of dollars were not on the table, probably nobody would have.

Thanks to Ken Stewart for his dedication.

SOURCE

Australian Politics

Australian Politics

Evelyn Rae, a conservative Australian political commentator

Evelyn Rae, a conservative Australian political commentator

Margo Robbie -- a beautiful australian

Margo Robbie -- a beautiful australian

My son Joe at ANU

My son Joe at ANU

One of the happiest pictures ever -- Cleo Smith, aged 4

One of the happiest pictures ever -- Cleo Smith, aged 4

No comments:

Post a Comment